Cozy Relations between South Korea’s National Election Commission and the Supreme Court Blur Separation of Power, Undermines Impartiality

2021-10-25, Tara O

The National Election Commission (NEC) in South Korea describes itself as “an independent constitutional body alongside the National Assembly, the Supreme Court and the Constitutional Court.” However, there is a strong connection between the NEC and the Supreme Court, and that is through the NEC’s chairman, who is also simultaneously a Supreme Court Justice. This arrangement blurs the line between the NEC and the Supreme Court, with accompanying consequences. The reputation of the NEC affects the reputation of the Supreme Court and vice versa, and this is problematic.

An example of this problematic structure is highlighted when the National Election Commission is brought to court as a defendant. In essence, the Supreme Court Justices must judge a fellow Supreme Court Justice, since a Supreme Court Justice is the head of the NEC, and this raises doubts about the Supreme Court’s impartiality, and in turn, the ability to hold the NEC accountable for the people.

The Supreme Court Violates Law

The law states that the court case shall be heard within 180 days. The 6-months deadline is not an option. The wording is “shall,” not “may.” So if the recount does not occur within 180 days (November 2020) after a lawsuit is filed, then the Supreme Court is violating the law. This is in fact what occurred.

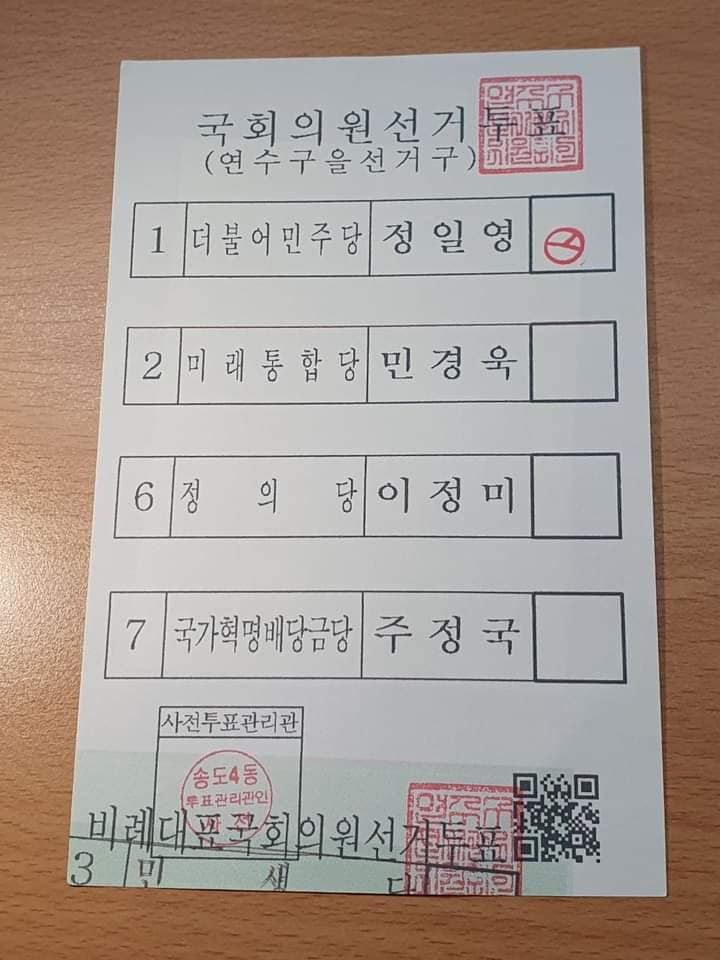

Of the 130 election fraud cases filed, the first examination of some of the election evidence was 413 days later (more than a year later), which was for Incheon’s Yeonsu-eul precinct. On May 7, 2020, former National Assemblyman Min Kyung-wook (민경욱) , then of Unified Future Party, who ran for office in that precinct, filed a law suit to examine the election evidence and nullify the April 15, 2020 election results of the Yeonsu-eul precinct in Incheon. On June 28, 2021, the Supreme Court’s Special Part 2, headed by Chief Justice Cheon Dae-yeop (천대엽), finally began a ballot review of the April 15, 2020 general election in Yeonsu-eul, Incheon. There were about 40,000 ballots to review at Yeonsu-eul precinct.

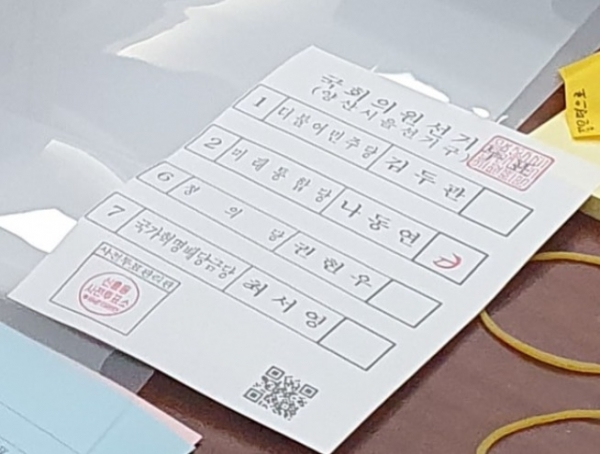

Only two other precincts—Yangsan-eul precinct in South Geyonggi Province and Yongdeungpo-eul precinct in Seoul—followed Yeonsu-eul in Incheon in examining the ballots. On August 23, 2021, the Supreme Court’s Special Part 2 (case led by Chief Justice Cho Jae-yeon, 조재연) began the examination of the ballots, which was attended by about 150 court staff, including 54 Supreme Court staff at the Ulsan region and 54 Supreme Court trial researchers.

The southern Seoul district of the Supreme Court began the ballot examination of Yongdeungpo-eul precinct in Seoul on August 30, 2021. Supreme Court Justice Cho Jae-yeon is also in charge of this case.

(Note: 13 of 14 current Supreme Court Justices were appointed by President Moon Jae-in.)

There were numerous calls since the filings in May last year, but the court took its time, and the examinations occurred for only 3 precincts. The court still has not made any decisions. This delay itself is a violation of the election law.

Evidence of Election Fraud at the Court

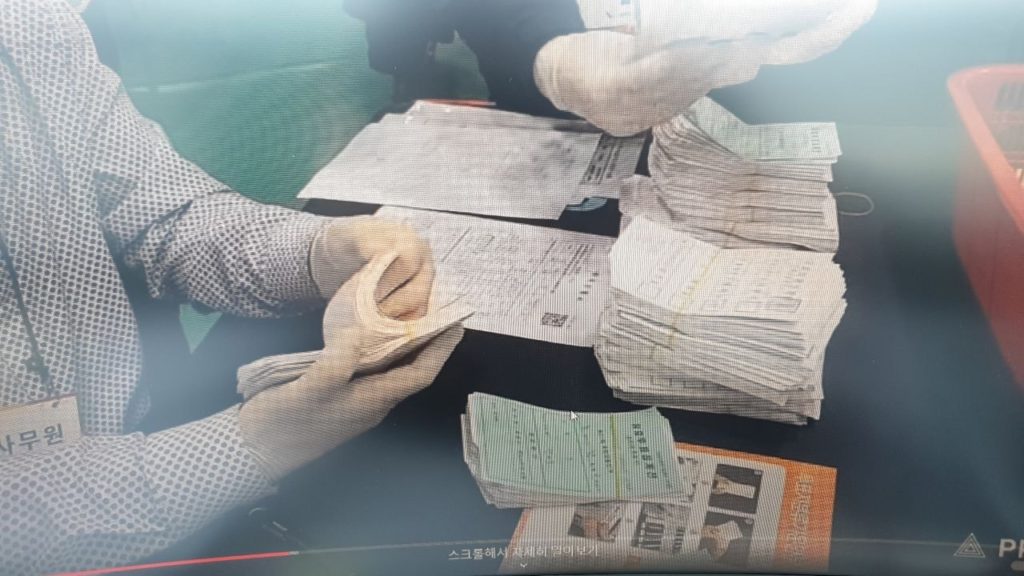

Thousands of ballots were questionable or were in conditions that were impossible to exist, if they met the rules (such as size of the margin, quality of the ballot papers, etc.) and the high standards expected of a modern Republic of Korea, and if the ballots went through normal handling process (such as touching the ballots by the voters). Yet the Supreme Court justices did not consider any of these ballots invalid.

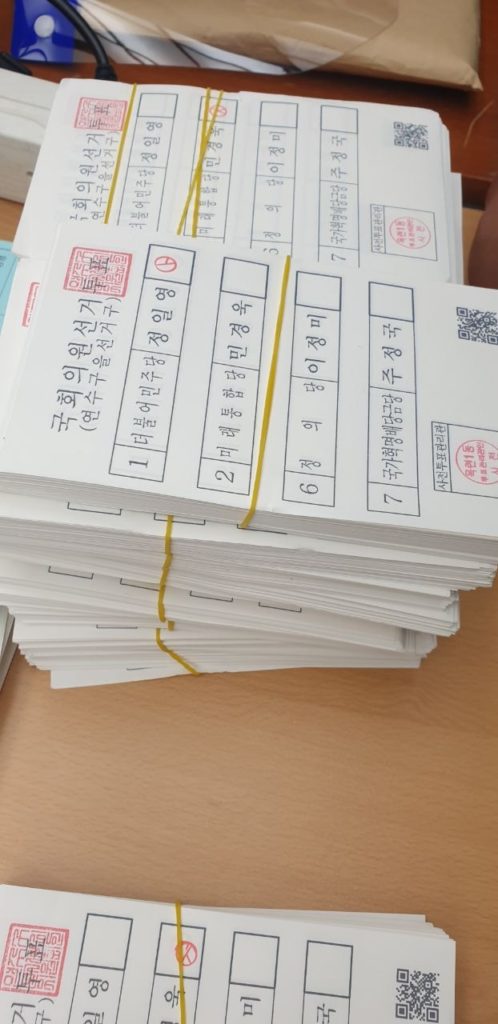

A large portion of the ballots, which were tied in stacks of 100, were stiff, similar to a stack of freshly minted dollar bills, raising suspicions that they were not the original ballots, but freshly printed for the purpose of the ballot examination to match the vote count. Former Prime Minister, former acting president, and the former leader of the United Future Party (prior to the People Power Party) Hwang Kyo-ahn, who attended these court sessions, said he saw at least 30-40% of the ballots were stiff ones. (47:28) The lawyers for the plaintiffs’ deputy group asked, “a book read once (by turning each page) looks like it was handled, so how can the ballots (which should have been handled by each voter) look so stiff and untouched?”

For comparison, ballots that went through the handling by the voters and ballot handlers look like the ballots below:

The National Election Commission made an absurd claim that the stiff ballots were due to the use of a special memory-paper that returns the ballot papers to the original state. In other words, the NEC is claiming that folded papers or handled papers would automatically go back to the original state of flatness and stiffness. No such paper exits. Even if such paper were to exist, it does not explain why there were some ballots that were folded as well—these should also have returned to the original stiff and flat state, but that was not the case.

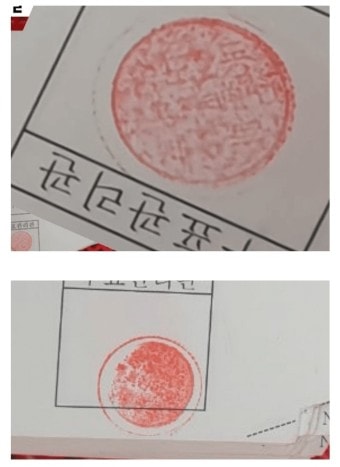

The ballots have stamps with the names of the local election managers showing that the ballots were validated at the time of the voting. These stamps are supposed to be round, but thousands of ballots had oval-shaped stamps. In Yangsan-eul precinct alone, about half of the 7, 362 ballots had oval-shaped stamps.

Hundreds of name stamps were also smudgy and it was impossible to read the names of the local election commissioners on the stamp. A normal stamp should clearly show the name that is easily legible, not a smudge.

There were also ballots that had yellow gluey substance normally used by large printing companies that kept some ballot papers together, like a bound notebook. Real ballots would be separate, not stuck together, because they are individually run through the vote counting machine. For pre-votes, the ballots are individually printed on site by a printer on the day of the pre-vote when the voter approaches to vote, so there is no reason any of the ballots, pre-votes and the day of votes, to be bonded together.

There were also ballots that had green color at the bottom of the ballot paper, with an image of the top portion of another ballot. This is termed a “cabbage” ballot, since Korean cabbage (for making Kimchi) is white with greenish leafy edges.

There also were ballots that were cut but taped back and soaked but dried ballots as well.

Some ballots’ margins were severely uneven on one side or the other. (3:47)

The weight of the paper the ballots were printed on was also problematic. According to lawyer Park Joo-hyeon (박주현), a printing specialist, who attended the ballot examination, noticed that the weight of a stack of ballots (100 ballots) should be 154 grams, but it was 264 grams. (3:24)

The plaintiffs lamented that these irregularities strongly suggest that fake ballots (low quality) were hurriedly printed prior to the ballot examination.”

For over 30 years, Hwang Kyo-ahn was a national security prosecutor, and prosecuting spies and election fraud fell in this realm. (20:54) As such, he is one of the leading experts in this field and knows the laws, what is considered evidence, and what an untransparent process looks like. He pointed out that these ballots that he himself observed at the ballot examination sites are evidence of election manipulation. Yet the Supreme Court Justices refused to categorize the problematic ballots as such.

Transparency problem

The citizens are pointing out the unfairness of the trial court. At the ballot examinations, the Supreme Court Justices initially prohibited taking photographs or videos of the ballots, many of which were questionable. The National Election Commission officials also tried to stop people from taking photos and videos or make it difficult for people to do so. There is nothing in the law that prohibits taking photos of the evidence, especially to share with the public, who have the right to know, yet the court refused steps for transparency, and sideed with the NEC, which doesn’t want transparency. The plaintiffs challenged by asking for precedence—none exists for this type of cases, and photos were taken, when possible. In trying to prevent taking photos, the Supreme Court justices broke the rules of trials for the public.

More delays

There were a series of one-person protests outside the ballot examination venues to demand transparency and fair elections. (The government has severely suppressed the freedom of assembly for those protesting election fraud in the name of COVID-19 prevention, but not the militant Korean Confederation of Trade Unions protests. Meanwhile, millions of people ride the subways in Seoul every day. See here, here, and here for more details on the suppression of freedom of assembly.)

The Supreme Court Justices have not made rulings on any of the above three cases yet. Still remaining are 126 more election fraud cases related to the April 2020 general elections in Korea. The Supreme Court, however, is delaying hearing these cases again. After numerous fake ballots appeared during the ballot examinations for the 3 cases, the Supreme Court delayed the hearing of the next case at Chungju, which was supposed to begin on October 2, 2021, to after next year’s presidential election (46:29). The presidential election will be on March 9, 2022. The court is signaling that it has no intention to try to improve the election processes or transparency before the next elections.

Lawyer Doe Tae-woo (도태우) on the Plaintiff’s side has gone on a hunger strike to protest the unfair and biased ways the Supreme Court is handling the election fraud lawsuits as well as its continuous and illegal delays. He stated “I condemn the grievous injustice displayed by the Supreme Court in the recent election fraud trials.”