Questions about the Incidents in May 1980 in Gwangju: Toll Road Ambush, Stealing Military Vehicles and Weapons, Rigging TNT in the Provincial Building

2022-5-18, Tara O

Raising a different version of events than the current narrative about what happened in Gwangju beginning on May 18, 1980 (“5.18”) or even questioning the account can land one in jail in South Korea. This is especially the case since the Democratic Party of Korea (Deobureo Minjoo Party) passed a law criminalizing it, in contradiction to the Republic of Korea’s constitution, which protects freedom of speech. The National Assembly also created a Truth Commission (for the third time, at least) on the issue, clearly indicating that this historical issue is not resolved. Besides, in a society dedicated to speaking truth, there should be debates about it, rather than a government commission concluding what the “history” is. Gwangju “5.18,” which used to be called the “Gwnagju Uprising,” “Gwangju Riot” and “Kim Dae-jung Rebellion,” but now often referred to as the “Gwangju Democracy Movement,” is an extremely divisive issue in South Korea, and a celebrated and praised issue in North Korea. Elevating it to a holy level and gagging the other side from talking about it does not bring people together. Strangely, those designated as “5.18 Meritorious Persons” are increasing in number as time passes, and getting the designation does not require actual physical presence in or near Gwangju. Naturally, the public demands to know who these people are, especially since their taxes provide lavish benefits for life to those designated as “5.18 Meritorious Persons.”

In search of the truth, the following questions are raised regarding events that occurred on one of the 10 days included in the Gwangju incident (“5.18”).

May 21, 1980

- The ambush at the Gwangju Toll Road. The prosecutors and the Inspector General of the Ministry of National Defense produced an investigative report “The Results of the Investigation of the 5.18 Related Events” (5.18 관련사건 수사결과) on July 18, 1995. According to the report, at 2:30 a.m., a convoy of 14 military vehicles, including jeeps, of the headquarters element of the 20th Infantry Division departed Yongsan station and drove down on Highway 1 (Geyongbu Highway), and were nearing an industrial area of Gwangju (near the toll gate) around 8:00 a.m., when the road was blocked by a demonstrating crowd. An officer got out of his vehicle and approached the crowd to try to convince them to move aside, but the convoy was ambushed from behind by an apparently well-trained group of people wielding metal pipes, sickles, and Molotov cocktails. Some of them disguised themselves as the police or ROK special forces by wearing their respective uniforms. They stole the military vehicles and left.

How did they know that the headquarters element would be passing through the Gwangju Toll gate and at that particular time? Where did they learn how to ambush? Why were some of them in disguise, as if they were friendly forces? Why did they steal the vehicles?

- Stealing APCs, other vehicles from Asia Motors in Gwangcheon-dong, the industrial area of Gwangju. The above group, after stealing the command element vehicles, then drove to the Asia Motors factory, a defense contractor, in Gwangcheon-dong, Gwangju, to steal military vehicles. They arrived there around 9 a.m. and were joined by about 300 additional people arriving there on 5 buses. They stole 4 armored personnel carriers (APCs) and about 370 military vehicles and buses within a few hours.

Who were they? This was at a time when most Koreans did not have cars and could not drive. Additionally, driving APCs and buses require a different level of skill than driving small cars. How could this group have an unusual number of people who can drive? How could so many of them know how to drive large vehicles and even APCs? Why, and how could they plan, organize, and prepare for so many people to steal vehicles so quickly?

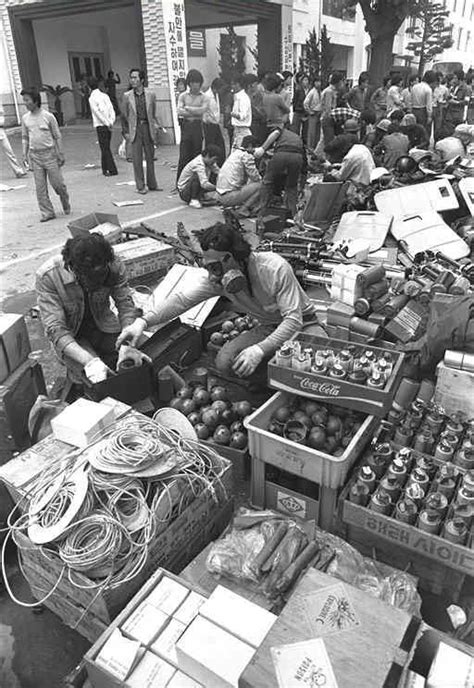

- Stealing weapons from armories. After stealing the vehicles from Asia Motors, they drove to 17 cities and counties in the province, and attacked and stole weapons from several dozens of armories. The prosecutor’s report show that they stole weapons, including 3,646 Carbines, 1,235 M1s, 34 M16s, 42 handguns, 51 crew served weapons, 395 civilian guns, 288,680 small arms ammunition, 2,180 tons of TNT/explosives, detonators, fuzes, 270 hand grenades, (407, Vol 1). (Prosecutors’ report, August 17, 1995). They took the stolen weapons to designated locations, began distributing the weapons, and conducted training on site to others.

How did they know the locations of the armories? How were they able to nearly simultaneously attack the armories? How did they know how to handle the various weapons? What were they going to do with that many weapons? Who organized and planned it? How did they know how to distribute weapons and train people?

- TNT rigged in the Provincial building. In the basement of the Provincial Office building, the armed (not the government) rigged 8 tons of TNT, and threatened to blow up the building if the government did not accede to their demands. At the time, there were two factions in the building—one that wanted all their demands met or else, and the other that was more moderate and was willing to turn in their weapons. The extreme faction suppressed the more moderate faction. Afraid, the moderate faction secretly contacted the Martial Law side and asked for help in de-rigging the explosives.

Rigging and de-rigging explosives require highly specialized training and is very dangerous. The military in the area had one explosive ordnance specialist, Bae Seung-il (배승일). The moderate side snuck Bae into the basement, where Bae began the difficult task of de-rigging. The atmosphere was tense not only because of the potential for explosion, but also because if they were caught by the extremist group, then their lives would be at stake. There was so much TNT rigged that he could not finish on the first day. Bae had to return the next day to completely de-rig all the TNT, thereby saving numerous lives of not only those in the building, but all nearby.

After the Gwangju incident was over, Bae Seung-il received an award for his meritorious service. After the retrials more than a decade later in 1995, which completely changed the narrative, Bae Seung-il, as part of the Martial Law forces, became vilified and his award rescinded. How did such a hero, who risked his life to save so many other lives, become dishonored when the narrative changed?

Who had the skills to rig the explosives? Those skills are rare.

Note: All the people in the photos handling the stolen weapons are not the South Korean military or police. Were they Gwangju civilians, North Korean special operatives, or others?

The ambush attacks at the toll gate, stealing command jeeps to go to the defense contractor, Asia Motors, then stealing a large number of military vehicles, including 4 APCs and buses, and using them to drive to various armories to steal weapons, then distributing and training others on the use of the stolen weapons—these extremely detailed tasks, some simultaneous, are the type of operations that special forces conduct after careful reconnaissance, planning, and rehearsals. All these acts were conducted in just one day, May 21, 1980. Rigging the TNT also requires specialized training and expertise, which most people do not have.

An armed group also attacked a prison in Gwangju six times, carrying on fire fights with the government forces, who were there to defend the prison. What kind of democracy are they promoting by armed attacks on a prison?

Who carried out these complex acts, which demonstrate strong indications of intelligence gathering, careful planning, and specialized military training, and experience conducting raids and ambushes? Were these acts really conducted by shoe shining teens and factory workers, in other words, people with little to no military training? How are these acts linked to “democracy?” These are only a part of what happened in Gwangju in May 1980, but they raise significant questions that require healthy public debates, not incarcerations, fines, and harassment.

This body of evidence is most impressive. I was at Osan Air Base when the uprising started, and I must confess I did not know many details at the time. I assume that United States Forces Korea and the United Nations Command wanted to avoid any appearance of collusion, notwithstanding the accusations made over the years. This event especially resonates with me, as my church group scheduled a religious retreat in Kyongju during the Memorial Day weekend. It was cancelled because of the turmoil and instability in the country, so I am most unsympathetic to the instigators of this insurrection.